Ted Corbitt started his running career as a

sprinter. On account of his inquisitive

attitude and desire to experiment, he gradually gravitated to exploring the

challenges presented by longer events. At age 31, in 1951, he set a goal of

training for his first marathon, Boston. That introductory 26.2 miles, on April

19 at age 32, saw him placing 15th with a time of 2:48:52. He did not hesitate long to attempt his next

marathon - the May 27 Yonkers Marathon. Few marathons existed to choose from

back then. This was a prestigious event. From 1938 to 1966,Yonkers served as

the annual national championship race for running’s governing body, the Amateur

Athletic Association (AAU).

Yonkers presented an extremely hilly and

challenging course, often with hot and humid weather. Ted placed 13th

in 2:48:58. Most people would consider racing two marathons with so little duration

between them as extreme. This did not seem to faze Ted. In fact, he raced a 10-miler ten days after

Boston and followed that up with a 5-mile handicap race on May 12.

In the early 1950s, the Olympic Committee used a

series of races to determine the marathon squad for the 1952 Helsinki, Finland

Olympic Team. Now there

is one qualifying Trials race. The top three make the team, provided each

individual has bettered a time standard established by the International Olympic

Committee. The three

races to be used as a basis for selecting the marathon team were:

Yonkers (National AAU

Championships), May 27, 1951

Boston, April 19, 1952

Yonkers, May 18, 1952

At the 1951 Yonkers race, Ted’s second ever

marathon, John Lafferty finished well ahead of the other Americans. Next year, on

a miserable sun-drenched 86-degree day in Boston, Corbitt was the third

American finisher behind Victor Dyrgall and Tom Jones. His time was 2:53:31. Four weeks later, Drygall and Jones again placed

ahead of Corbitt at the hilly Yonkers’ course.

Ted’s time there was 2:43:23. He was quite satisfied because, along with

a personal record time, he was battling a severe hamstring injury, which he suffered

six days prior to the race.

Originally, Drygall and Jones, along with John

Lafferty, who had decisively beaten the others in the 1951 Yonkers’ event, were

named to the Olympic team. However, here is an explanation from the selection

committee’s notes that I came across as to how the ultimate three-member team,

which included Corbitt, was determined.

'Upon recommendation of the Marathon sub-committee,

a selection plan similar to that in effect for the '48 OG's was adopted. Under

this plan, the US Marathon championships of '51 & '52, together w/the

Boston Marathon of '52, were designated 'qualifying races' w/the winner of the

'52 Championship (if eligible) and two others w/the 'best average races' in all

3 races to be selected for the Olympic team. Victor Dyrgall of NY, winner of

the '52 Championship and Tom Jones, who had finished 2nd, 2nd & 3rd

respectively of the eligible Americans in the 3 races, were clearly entitled to

selection.

There was, however, a difference of opinion in the sub-committee as to the third man for the team. John Lafferty of Boston had finished 2nd in the '51 race and 11th and 5th in the '52 races. Ted Corbitt of NY had finished 13th in '51, and 6th and 3rd in '52. The dispute was as to the method of scoring. Eliminating only eligible foreign athletes from the scoring would give Lafferty the better score of 14 (2-7-5) to Corbitt's 16 (10-3-3). Elimination of all except those who had run in all three races (as was done in '48) put Corbitt ahead of Lafferty 10 (6-2-2) to 11 (1-6-4).

The full committee at its meeting in Long Beach, CA, all coaches and managers of the team present, unanimously decided in favor of Corbitt, not only on the basis of past interpretation but also on the extremely practical ground that, whereas Lafferty had been better than Corbitt in '51, Corbitt had beaten Lafferty in both races in '52, when the Olympic Games were going to be held.

It is recommended that selection of Marathon runners for future Olympic teams be based solely upon performance during the year of the Games and that whatever method is used be clarified as to scoring.

There was, however, a difference of opinion in the sub-committee as to the third man for the team. John Lafferty of Boston had finished 2nd in the '51 race and 11th and 5th in the '52 races. Ted Corbitt of NY had finished 13th in '51, and 6th and 3rd in '52. The dispute was as to the method of scoring. Eliminating only eligible foreign athletes from the scoring would give Lafferty the better score of 14 (2-7-5) to Corbitt's 16 (10-3-3). Elimination of all except those who had run in all three races (as was done in '48) put Corbitt ahead of Lafferty 10 (6-2-2) to 11 (1-6-4).

The full committee at its meeting in Long Beach, CA, all coaches and managers of the team present, unanimously decided in favor of Corbitt, not only on the basis of past interpretation but also on the extremely practical ground that, whereas Lafferty had been better than Corbitt in '51, Corbitt had beaten Lafferty in both races in '52, when the Olympic Games were going to be held.

It is recommended that selection of Marathon runners for future Olympic teams be based solely upon performance during the year of the Games and that whatever method is used be clarified as to scoring.

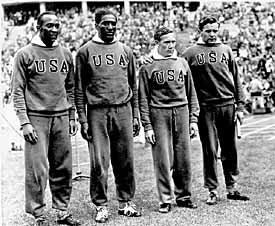

With his Olympic status came the distinction of

becoming the University of Cincinnati’s first track and field Olympian. Ted was

also the first African-American to represent the USA in an Olympic Marathon. His next marathon was to be in Helsinki on

July 27.

Ted Corbitt posing in front of the Paavo Nurmi statue, immediately in front of the Helsinki, Finland Olympic Stadium. Nurmi, world record holder and winner of multiple Olympic medals is a national hero.

Corbitt, with only five marathon completions coming

into the Games, was still a novice at this distance. There is a picture of Emil Zatopek, who went on to

win his third distance event of the 1952 Games, leading the pack after exiting

the Olympic Stadium. The photo shows Ted in about 15th place. Perhaps his early pace was too fast. We do know that his performance there was less than what he hoped

for as he came, with a 2:51:09 time, in 44th place out of 53 finishers. Of the other two Americans, Dyrgall ran 2:32:52 to place 13th and Jones’ 36th

took 2:42:50 to complete.

Years after he ran in the Helsinki Olympics a man

roughly the same age as Ted came over and gave him a hug. Ted didn’t recognize

him, but the man introduced himself and mentioned that they had both competed

in one of the 1952 U.S. Olympic Marathon Trials’ races. The man then became

somber. He said that he wanted to make a long-overdue apology. It seems that at

the race, this individual and a few others decided that a black man shouldn’t

be allowed to represent the United States at the Olympics. They made a secret

pact to prevent Ted from making the team. “We boxed you in, we kicked you, we

tried to trip you, we did everything we could to take you down, but you managed

to get away and win that spot. I’ve regretted my behavior for years, and I just

wanted to say that I am sorry for what I did.” Ted, who by nature was very

forgiving, replied, “You guys gave me a great run. If it weren’t for you, I may

not have run so fast.”

For Corbitt the Olympic experience,

other than his final placement, was fulfilling. He came away with a new

appreciation for training, having witnessed Emil Zatopek’s greatness, as the

Czech swept all three distance running gold medals in those Games. Ted resolved

to implement some of Zatopek’s exhaustive interval and strength training into

his already extensive program. To use a

trite expression, we can say that the rest is history.