Jesse Owens’ Shadow – “Sam Stoller”

Imagine being part of a great rock and

roll band, but your career paralleled The Beatles. Imagine being an honor roll student, but

there was a guy named Einstein seated in the adjoining row. Imagine being a gifted artist, but an individual

named Picasso was in your group. Imagine

being an outstanding sprinter while in high school in Ohio, while

attending a Big Ten university, and

while on the U.S. Olympic team, but there was a fellow dash man named Jesse

Owens. This was Sam Stoller’s fortune,

or misfortune, as a runner and long jumper.

Sam in his Hughes uniform

Sam in his Hughes uniform

A

1933 graduate of Hughes High School and a 1937 graduate of the University of

Michigan, Sam Stoller led a fascinating life of champion and runner-up, of

Olympian and non-Olympian, of athlete and singer. Sam was born in Cincinnati and attended

Hughes High School at the same time that Jesse Owens was running in

Cleveland. As a result, Sam never won

the state meet in high school, finishing second to the great Jesse Owens who

ran for Cleveland East Tech. The two

followed each other to the Big Ten where Stoller continued to be a frequent

runner-up to Owens. Sam ran for the

University of Michigan while Jesse competed for Ohio State. During their college days they faced each

other 20 times with Sam winning only once, yet the races were always

close. Sam once said, “I’m the fellow

you see in the movies of Jesse’s footraces.”

Jesse

Owens burst onto the national stage when he set four world records at the 1935

Big Ten Championships. Sam made his

national mark for the first time by tying the world record for the 60-yard dash in 6.1 seconds at the 1936 Big Ten indoor

championships.

Yet,

it was in the 1936 Olympic Trials followed by the Berlin Olympic Games where

the two earned lasting recognition. Stoller, after John Anderson (1928

and 1932), became the second Hughes graduate to qualify for an Olympic track

and field team. Jesse immortalized himself by winning four gold medals

in the historic “Hitler Olympics” whereas Sam became best known for qualifying

for the USA 400-meter relay, then being denied the opportunity to run. Considerable controversy surrounded that

decision at the time and even to the present.

At

the 1936 Olympic Trials at Randall’s Island in New York City, the final places for

the 100-meters were as follows: 1. Jesse

Owens, 2. Ralph Metcalf, 3. Frank Wykoff, 4. Foy Draper, 5. Marty Glickman, 6. Sam Stoller and 7. Mack Robinson (brother

of Jackie Robinson). Using the logic and

current thinking of United States sprinting, the top four would run the finals

of the 400-meter relay while fifth and sixth would serve as backups, running

only in the preliminary trials. However,

at that time, 1936, the plan was to have the headliners run the open sprints

and to have the others concentrate on their handoffs, directing their entire

attention to the relay. This is the way it was done in

1932. In 1936 the two open 100 runners, Ralph Metcalfe and Jesse Owens, were

aware that they would not be called to run in the relay. Consequently Stoller rode the Olympic

ship to Germany fully planning to run the 400-meter relay.

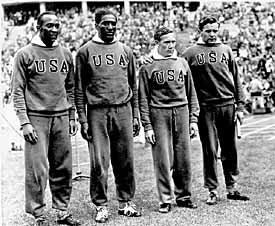

Original relay team on the ship traveling to Europe

L-R Foy Draper, Marty Glickman, Sam Stoller, Mack Robinson

Once

in Germany the team of Sam Stoller, Marty Glickman, Foy Draper and Frank Wykoff

practiced their handoffs faithfully in anticipation of the day when they would

represent the USA. There might be a question as to

why Wykoff, rather than Robinson, was designated for the relay. Wykoff had

qualified as an open 100 runner and Robinson had done the same in the 200. The

200 was considered more strenuous than the 100. In addition, Wykoff had Olympic

relay experience. He was on the winning world

record teams of the 1928 and 1932 Olympiads. Almost from the beginning, Frank Wykoff

was considered the anchor man for the team.

While

in Berlin, the U.S. coaches supposedly heard a rumor that the Germans were

hiding their best sprinters so they could surprise the world, especially the

Americans in the 400-meter relay. However, in the 100 and 200-meter races they

were nowhere to be seen. This

is regarded as a lame excuse at best.

Near the end of the Olympic Games, and the morning of the 400-meter

relay trials, a hurried meeting took place with U.S. head coach Lawson

Robertson, assistant coach Dean Cromwell and the seven American sprinters. This meeting is portrayed in the movie “Race”, which is about Jesse

Owens. In that meeting it was announced that Owens and Ralph Metcalfe,

who had placed first and second in the 100 meters, would replace Stoller and

Marty Glickman. The logic explained during

that meeting was that the coaches wanted to put the four fastest runners on the

relay.

This is how it is done in 2016, but it

was not the custom at the time. Neither Owens

nor Metcalfe had practiced baton exchanges with the others while in

Germany. The ability to rapidly and

safely pass the baton is an important component of the event. Even though the raw speed of the original

team was slightly inferior to the one with Jesse and Ralph, Frank Wykoff felt

that their exchange practices would allow the original foursome to move the

baton around the oval as fast or even quicker than with the substitutes.

Favoritism is another possibility as to

why the switch was made. In

a recent 100-meter runoff just prior to the trial heats, Stoller and Glickman finished

ahead of Draper. This indicated that the two who were removed were faster than one

who did compete, which

counters the argument that the coaches were only interested in the fastest

quartet. Coincidently, both Draper and Wykoff ran for Cromwell at the

University of Southern California.

The theory most believed, and the interpretation

by the two runners left off the relay, is that they were dropped for religious

purposes since they were both Jewish and the US Olympic Committee did not want

to offend Hitler and the Nazi leaders.

Both Avery Brundage, the Head of the USOC, and assistant coach, Dean

Cromwell, were members of the American First Committee, an isolationist group with

anti-Semitic leanings. Charles Lindbergh headed the organization. Many feel that the directions to

change the team flowed down from Brundage. He presented a favorable Nazis point

of view on several occasions. Glickman,

who was more vocal than Stoller about the rationale for the decision, offers

his opinion in a short video: https://youtu.be/F87h1vzv_vY

It

was Stoller’s 21st birthday and he could not will himself to go to

the magnificent stadium that Hitler constructed to witness the relay race that

he believed he should have been a part of. Sam vowed never to run again.

However,

he reconsidered and ran during his final year at Michigan. Since Owens did not return for his

senior year at Ohio State, Stoller dominated the dashes during that season. He won both the Big Ten and NCAA 100-yard dash titles. This required a change from the headlines

of articles that previously read, ‘Second, Stoller.’

After

the NCAAs in 1937, he stayed in California, taking up a singing career in nine

separate movies as Singin’ Sammy Stoller.

Later in life he was an announcer for the Washington Senators. In 1988 the US Olympic Committee tried to

atone for the Olympic slight by awarding Stoller and Glickman the General

MacArthur Medal. Sam Stoller was also

inducted into the International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame before dying in 1985

at the age of 69.

The

team of Jesse Owens, Ralph Metcalf, Foy Draper and Frank Wykoff went on to win the gold

medal in the world record time of 39.8.

However, the controversy continues today.

The Gold Medal Quartet

L-R (photo and order of running)

Jesse Owens, Ralph Metcalf, Foy Draper, Frank Wykoff

No comments:

Post a Comment